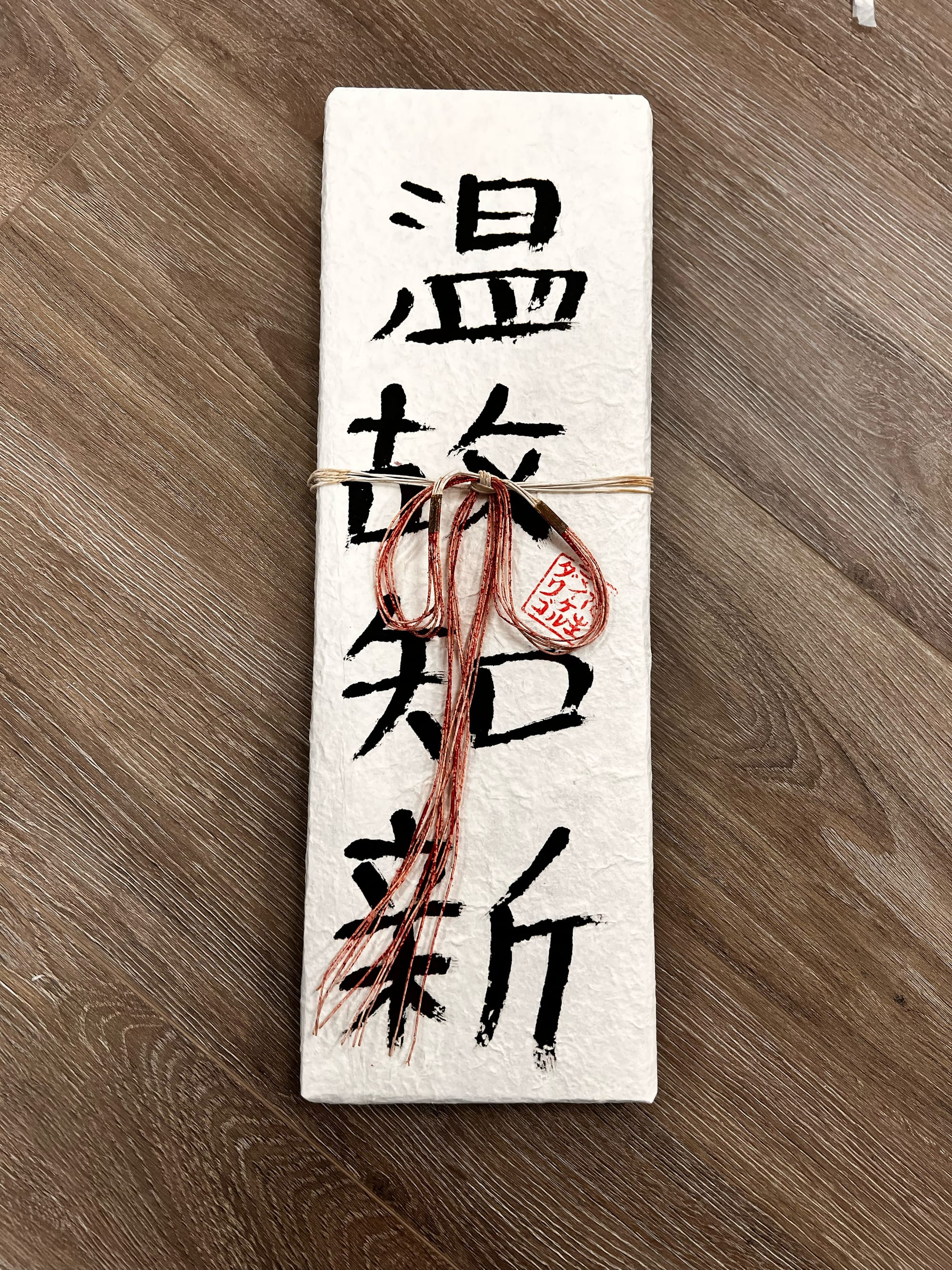

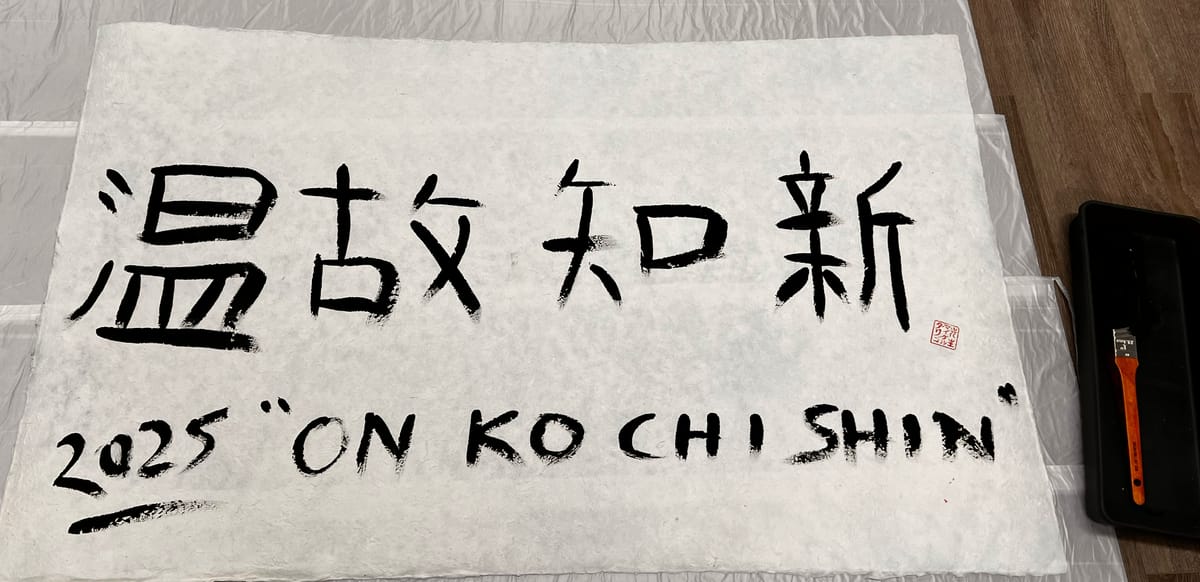

Onkochishin 温故知新 offers a powerful framework for personal development as it reminds us to mine the past — both our own and that of history — for new wisdom and insights. It was chosen as the Kagami Biraki lecture for 2025.

Onkochishin 温故知新 [pronounced: on-koh-chee-shin] offers a framework for growth that transcends cultures and time periods. This ancient concept, which emphasizes mining the past for new wisdom, provides insights for both personal development and organizational growth. By understanding how this principle has shaped disciplines from martial arts to philosophy, we can better apply its wisdom to our modern challenges.

General History can help us build the future, but even more importantly, it tells us who we are today.

Onkochishin 温故知新 also continually prods us to review our personal history to sharpen our understanding of our present, and ourselves.

Armed with that wisdom of self-identity and self-awareness today, we are better equipped to build the tomorrow we desire.

Personal Development: Mining the Past for Future Growth

Onkochishin 温故知新 offers a powerful framework for personal development. We are incredibly fortunate to have a body of experience from our past that we can use to learn more about ourselves. That knowledge gives us an insight into what works and what doesn’t work for us in striving to achieve our goals and develop our skills, knowledge, and strong spirit.

There are many aspects to this review of the past.

Probably the most important is to consider the goals, aspirations, and sense of purpose and identity that we have developed in the past. Are we living up to those ideals? Are we living that identity? Or are we forgetting the contours of the self-identity we have designed for ourselves, and instead allowing the press of events and passage of time to make that identity a murky imitation of what we set out to have.

Consider how you saw yourself five or ten years ago. Or even father into the past, when you were a young adult just beginning to define yourself. Has your self-identity evolved with time? Is that evolution something that occurred under your control, or was the change in your self-identity less evolution and more disrepair or from a lack of focus?

In our rush toward self-improvement, we often chase the newest techniques, latest books, or most recent psychological theories. Yet, the principle of Onkochishin 温故知新 suggests that true growth comes from first understanding the fundamental wisdom that has stood the test of time; and it also comes from maintaining a strong focus on our fundamental purpose, identity, and goals.

Onkochishin 温故知新 manifests this growth in several ways:

First, it encourages us to study our own past experiences deeply. Every success and failure contains lessons that, when properly understood, can guide future growth. Rather than simply moving on from mistakes, Onkochishin 温故知新 advocates examining them thoroughly to extract their teaching value.

Second, it promotes the study of historical figures and traditional wisdom. While modern self-help literature offers valuable insights, the enduring principles found in classical philosophy, literature, and spiritual traditions often provide deeper, more nuanced understanding of human nature and personal development.

Third, it teaches us to approach new information and techniques with both openness and discernment. By understanding traditional principles deeply, we develop a framework for evaluating new ideas and integrating them meaningfully into our practice.

From the Personal to the Macro

All of this applies equally to organizations as well as ourselves. Companies, non-profits, and even entire countries and cultures can lose sight of their self identity and forget their own history.

And yes, even a dojo or an entire martial art, can lose sight of its core identity as well.

Onkochishin 温故知新 instructs us to both preserve the history, core ideas and values, and institutional wisdom that is inherent in organizations and cultures. But whether that culture is a company culture or the culture of an entire people, we are also urged to evolve and extend that core to accommodate the present day and the contemplated future.

Just like people, companies and nations that do not evolve eventually ossify, grow creaky and rusty, and eventually collapse of their own inertia.

We need to challenge ourselves and grow through that challenge. And we need to evolve our skills, thinking, and experience. And so do companies, organizations, and even nations.

The Integration of Old and New

The genius of Onkochishin 温故知新 lies in its rejection of false dichotomies between tradition and innovation. It suggests that true progress comes not from choosing between old and new, but from using deep understanding of the past to inform future development.

For a dojo, this might mean using modern science to better understand why traditional training methods work, or adapting ancient principles of strategy to address contemporary self-defense scenarios. But while doing this, it is important to preserve, protect, and extend the core traditional wisdom that defines the very identity of a dojo and its martial art.

In personal development, it could involve using modern psychological research to better implement traditional mindfulness practices, or applying ancient wisdom about human nature to navigate modern technological challenges. We are incredibly fortunate to have access to an incredible amount of research and opinion into productivity and accomplishment: yet, we must be up to the challenge of integrating this wisdom into our own life. And we must also curate this information because not everything masquerading as wisdom is actually worth valuing and internalizing.

History is a Guide, Not a Recipe

Mark Twain, the famous American writer, said that “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it often does rhyme.” His point is well-taken: we should not expect that what comes next is a an exact duplicate of what came before.

This can be an amazingly hopeful message for our own life. Yes, certainly, our personal history helps us to understand ourselves and to shape the future. But our past need not be a straightjacket that forces us to repeat past mistakes — rather it can be a guide to avoiding those mistakes.

We are not fated to repeating our history: we can change, and we can follow a different path in the future, although doing so means making a specific and conscious decision to do so.

The Martial Way: Preserving While Evolving

In martial arts, Onkochishin 温故知新 manifests in the delicate balance between preserving traditional techniques and adapting to contemporary needs. The kata passed down through generations contain not just physical movements, but encoded principles of combat, strategy, and human biomechanics. These forms serve as living textbooks, preserving the hard-won insights of past karateka.

However, true mastery requires more than mere preservation. A karateka practicing Onkochishin 温故知新 studies these ancient forms not as rigid dogma, but as springboards for deeper understanding. By thoroughly examining why techniques were developed, what problems they solved, and how they work with human psychology and physiology, the karateka gains insights that can be applied to modern contexts.

Consider the evolution of traditional Japanese jujutsu into modern judo and Brazilian jiu-jitsu (developed in the early 20th century). The core principles of leverage, balance, and efficient movement remained constant, while the application evolved to address new challenges and contexts. This represents Onkochishin 温故知新 in action - respecting the wisdom of the past while adapting it for the present.

In karatedō, we have seen the evolution of ippon kumite to address weapons, and we have further thought deeply about kata to understand and defeat new types of adversaries as well as traditional adversaries with new techniques.

And most importantly of all, we have adopted and adapted the philosophical underpinnings of karatedō to address modern present-day challenges and opportunities.

Historical Origins: Asia

The concept of Onkochishin 温故知新 seems to have arisen simultaneously in both Asia and the West.

The literal phrase Onkochishin 温故知新 originates from the Analects of Confucius (551-479 BC), specifically from Chapter 2, Verse 11: "温故而知新,可以為師矣". This can be translated as "If by studying the old, one comes to understand the new, one is worthy to be a teacher." The concept emerged during China's Spring and Autumn period (771-476 BC) and later spread throughout East Asia, becoming particularly influential in Japan.

As Buddhism and Confucian thought spread through East Asia, this concept became deeply embedded in Japanese cultural and educational traditions, eventually finding its way into martial arts philosophy during the Kamakura period (1185-1333 AD). The principle became especially important during the Edo period (1603-1867 AD), when many martial arts schools (ryūha) were systematizing their teachings and creating formal transmission methods.

Historical Origins: Ancient Greece

While Confucius was developing the concept of Onkochishin 温故知新 in the East, Ancient Greece was cultivating remarkably similar philosophical approaches to learning and development. The Greek concept of "archaia sophia" (ancient wisdom) and its relationship to new knowledge was particularly evident in the works of Plato (428-348 BC) and Aristotle (384-322 BC).

But even earlier, Thucydides (460-400 BC), in his seminal work "History of the Peloponnesian War," articulated a principle strikingly similar to Onkochishin 温故知新. He wrote that his work was meant to be "a possession for all time" rather than just a prize composition for the moment, stating that those who want to understand "the clear pattern of human behavior" should look to the past. His famous assertion that his histories would be valuable to those who wish to understand "the similar patterns which could be expected to happen again in the future" parallels the core concept of Onkochishin 温故知新 - that studying past patterns reveals insights applicable to future situations.

Plato's dialogues, written in the early to mid-4th century BC, frequently explored the idea that true knowledge comes from examining and building upon the wisdom of the past. In his work "Timaeus" (circa 360 BC), he presents the story of ancient Athens and Atlantis, suggesting that by studying ancient histories, we can gain new insights into governance and society. This mirrors the fundamental principle of Onkochishin 温故知新 - that reviewing the old reveals new understanding.

The Greek gymnasium system (developed from the 6th century BC onwards) combined martial training with philosophical education and embodied this principle in practice. The pankration and wrestling schools preserved techniques dating back to mythological times while continuously evolving their methods. Historical records from the ancient Olympics (776 BC - 393 AD) show how wrestlers would study traditional holds and movements (palaia) while developing new variations (kaina) - a process strikingly similar to the Japanese concept of henka-waza (“variations on a technique”).

Aristotle's approach to knowledge building, outlined in his "Metaphysics" (written around 350 BC), particularly resonates with Onkochishin 温故知新. He emphasized that new knowledge should be built upon careful examination of previous thinkers' works, stating "The investigation of the truth is in one way hard, in another easy. An indication of this is found in the fact that no one is able to attain the truth adequately, while, on the other hand, no one fails entirely, but everyone says something true about the nature of things."

In the martial context, the Greek hoplite training system (developed from the 8th century BC, some two centuries before Confucius wrote) demonstrated this philosophy in action. Traditional phalanx tactics were preserved and studied, while new variations were developed to meet evolving battlefield conditions. The Greeks maintained detailed records of both successful and failed military strategies, creating a knowledge base that commanders would study to develop new tactical innovations - a practice that perfectly embodies the principle of Onkochishin 温故知新.

Integration into Traditional Karatedō

The adoption of Onkochishin 温故知新 into Japanese martial traditions occurred gradually, becoming particularly prominent during the transition from wartime to peacetime martial arts.

During the Sengoku period (1467-1615 AD), martial arts were primarily focused on battlefield effectiveness, with techniques passed down through direct combat experience. However, as Japan entered the relatively peaceful Edo period (1603-1867), martial arts schools faced a crucial challenge: how to preserve and transmit combat knowledge without regular battlefield experience.

This challenge led to the development of sophisticated teaching methodologies that embodied Onkochishin 温故知新.

The founders of major schools like Yagyu Shinkage-ryu (founded 1566) and Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū (founded 1447) began documenting their art in detailed technical manuals (densho). These weren't mere technique catalogues, but contained layers of meaning - physical techniques (jutsu), underlying principles, and philosophical concepts that could be discovered through dedicated study and practice.

The kata system itself became a prime example of Onkochishin 温故知新 in action. Rather than just preserving specific techniques, kata were designed as living repositories of tactical principles.

For example, the Kōyō Gunkan, a military manual of the Takeda clan (compiled 1616 AD), emphasizes how studying old kata reveals new applications: "Within the old forms lie the seeds of new techniques." This approach allowed martial artists to adapt to new challenges while maintaining their connection to proven principles.

During the latter half of the Edo period, many ryūha (schools) developed the concept of "henka-waza" (variation techniques), which explicitly demonstrated how traditional forms could generate new applications. This practice showed students how to extract core principles from classical techniques and apply them in novel situations - a direct manifestation of Onkochishin 温故知新.

The transformation of martial arts during the Meiji Restoration (which began in 1868) provides perhaps the most dramatic example of Onkochishin 温故知新 in practice.

As Japan modernized, martial arts had to adapt or risk becoming obsolete. The founders of modern arts like Judo (founded 1882) and Aikido (developed in the 1920s) demonstrated Onkochishin 温故知新 by preserving the essential principles of traditional combat while adapting them to serve new social and educational purposes.

Jigorō Kanō (1860-1938), the founder of Judo and one of the most important influences on modern karatedō, explicitly cited Onkochishin 温故知新 as a guiding principle in his development of Judo from traditional Jujutsu, stating that "nothing under the sun is really new" and that innovation comes from deeper understanding of traditional principles.

And for the traditional martial art of karatedō, all the modern founders of various schools of karatedō built their teaching of kihon waza (basic techniques), kata, and karatedō (the underlying philosophy of karate) on the historical teachings they had received by their teachers and the sources of learning that their teachers learned from. (As an example, see the origin of Yansu Kata).

A Deeper Look into the Kanji in Onkochishin 温故知新

The individual characters that compose Onkochishin 温故知新 each carry deep meaning: '温' (on) means to warm or review, '故' (ko) refers to old things or matters, '知' (chi) means to know or understand, and '新' (shin) represents the new or novel.

Together, they suggest that by "warming up" or reviewing old matters, we can discover new insights and understanding. This metaphor of "warming" is particularly significant, as it implies not just mechanical review but a process of breathing new life into old knowledge.

Wisdom and Innovation

Onkochishin 温故知新 reminds us that genuine advancement - whether in martial arts or personal growth - requires both reverence for traditional wisdom and openness to innovation. By studying the past deeply while remaining receptive to new insights, we can create meaningful progress that builds upon, rather than discards, the lessons of history.

This approach offers a middle path between blind traditionalism and thoughtless modernization. It suggests that the best way forward is to stand firmly on the shoulders of those who came before us while reaching toward new horizons.

In doing so, we honor both the wisdom of the past and the potential of the future, creating a more integrated and profound approach to development in all areas of life.

| Kanji/Katakana | Meaning |

|---|---|

| 温 | to warm or review (on) |

| 故 | the past (ko) |

| 知 | knowledge (chi) |

| 新 | new (shin) |

Editor's Note: This lecture has been delivered by Sensei in New York City at the Goju Karate dojo on 18 January 2025 as the Kagami Biraki lecture for 2025.

![Ikioi — Momentum 勢い [Edition 2025]](https://images.unsplash.com/photo-1691568520168-d74572f43f62?crop=entropy&cs=tinysrgb&fit=max&fm=jpg&ixid=M3wxMTc3M3wwfDF8c2VhcmNofDYyfHxtb21lbnR1bXxlbnwwfHx8fDE3NDczNDY5MDJ8MA&ixlib=rb-4.1.0&q=80&w=720)

![Taikibansei — Great Talent, Evening Forming 大器晩成 [Edition 2025]](https://images.unsplash.com/photo-1534447677768-be436bb09401?crop=entropy&cs=tinysrgb&fit=max&fm=jpg&ixid=M3wxMTc3M3wwfDF8c2VhcmNofDIzfHxzaG9vdGluZyUyMHN0YXJ8ZW58MHx8fHwxNzQ0MTU3MTQzfDA&ixlib=rb-4.0.3&q=80&w=720)